Urn Game

Suppose a game for you and another player, where in the beginning you receive 80$ and the other player 20$. The objective is simple – you have 100 candy bars to buy and you want to buy as many as possible more than your friend. But there are three rules:

-

Each time step, both players need to try to buy a candy bar, and you have to play until you spend all your money.

-

In order to try to buy one candy bar you need to spend \(\Delta m\).

-

You can’t choose the candy bar. You can only pick one randomly at each time step and if that bar has already been chosen before, by you or your opponent, you will lose your \(\Delta m\).

Since you have much more money than your opponent, you probably will be able to buy more chocolate than him. Is this true no matter \(\Delta m\)? The naive reasoning let you believe that in the end of the game, if you add the total number of chocolates bought, 80% will be yours and only 20% will stay for your friend.

However, things are not so simple. Imagine the case when \(\Delta m \to 0\). At that point, you and your friend will have almost the same purchase power. Therefore, in the end you will get 50% of the chocolate just like your friend, which is not good for you.

For the other extreme you can only go up to \(\Delta m = 80$\). At this point, you can buy one candy bar and your friend none. This is good for you, but this is probably not the best. How much more can you buy than your friend in function of \(\Delta m\)? The precise answer is,

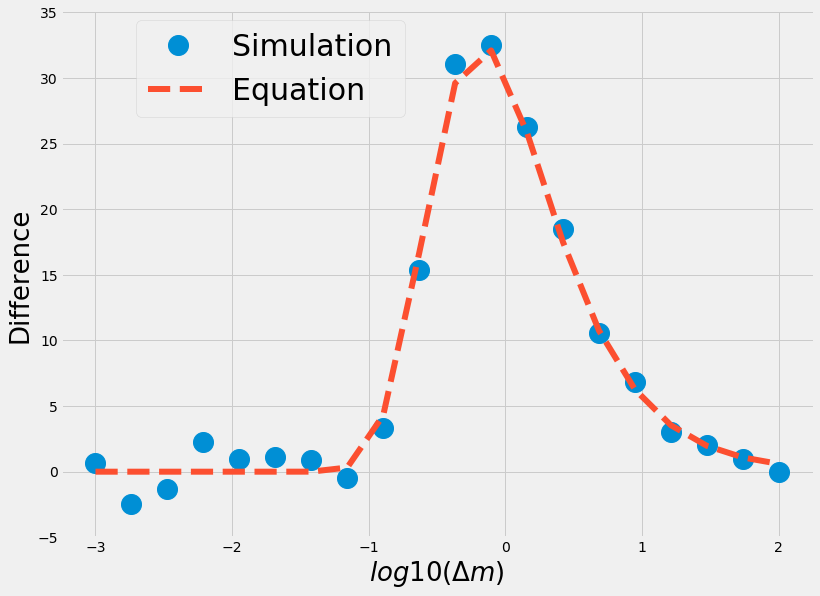

\[100 (e^{-0.4/\Delta m} - e^{-1/\Delta m})\]You can easily simulate this and check by yourself that this formula fits correctly in the average behavior. I show in the figure bellow the average for 20 simulations and the behavior of the difference between your candy bars and those of your friend.

But what about a more generic game? If you have \(N\) candy bars, and you start with \(m_y\) money, against \(m_o\) of your opponent. The difference is,

\[N (e^{-2m_o/(N \Delta m)} - e^{-(m_y+m_o)/(N \Delta m)})\]I will not demonstrate this formula now, but if you are really curious, you can go

to the supplementary material of our paper.

The most interesting thing is not just the fact that there is an optimal \(\Delta m\) for you, but also

that this simple model can be used to understand the final result of an election. This connection

will be here in future posts.